In 2001 the Productivity Commission released a report into the competitive neutrality of the State government forest agencies in Australia.

http://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/forestry

The report makes for interesting reading 15 years after it was published.

So what is competitive neutrality?

Competitive neutrality (CN) means that state-owned and private businesses compete on a level playing field. This is essential to use resources effectively within the economy and thus achieve growth and development.

CN policy forms part of the 1995 Council of Australian Governments’ agreement on National Competition Policy (NCP).

CN policy aims to promote efficient competition between public and private businesses. Specifically, it seeks to ensure that government businesses do not enjoy competitive advantages (or suffer from a competitive disadvantage) over their private competitors simply by virtue of their public ownership.

The fact that the Productivity Commission felt the need to write such a report says a great deal about the forest industry in Australia. Remember this was in 2001 immediately after the Regional Forest Agreements (RFA) had been completed and signed.

Why weren’t competitive neutrality issues covered as part of the RFA reforms?

It is certainly my belief one of the major reasons we don’t have a thriving blackwood industry in Tasmania is the absence of competitive neutrality.

Here’s my precise of the report by chapter, and what I regard as some of the more salient points from a blackwood growers perspective.

1 Introduction

Forest products industries source wood from both public and privately managed forests, although public forests have traditionally accounted for the overwhelming bulk of wood supplies.

The situation has changed dramatically over the past 15 years with most wood grown and sold in Australia now coming from private forest growers. But State forest agencies continue to exert a significant influence on the industry especially around policy and politics.

Also the privatization of public plantation assets has introduced new distortions in the marketplace such as new owners being exempt from paying local Government rates and charges, competing against other private forest growers who do pay rates and charges. Local communities are now forced to subsidize the new private forest owners.

As forestry agencies are deemed to be significant government businesses, they are subject to CN. This requires them to:

- charge prices that reflect costs;

- pay all relevant government taxes and charges;

- pay commercial interest rates on their borrowings;

- earn commercially acceptable returns on their assets;

- and operate under the same regulatory regime as their private sector counterparts.

To this list I would add:

- receive no direct or indirect taxpayer subsidies;

- harvest all timber on a fully commercial basis. Undertake no community service timber harvesting;

- provide complete and separate annual accounts for all Government-funded community service activities (CSOs).

There would certainly be other CN principles that could be added to this list.

2 Forestry background and institutional framework

Competitive neutrality is about a level playing field but the report provides little insight into the nature of the forest industry playing field and the numerous factors that impact the quality of the playing surface. For example there is a section in Chapter 2 discussing employment in the forestry sector, but no discussion on how sector employment impacts CN and the quality of the playing surface!

Chapter 2 provides a background summary of the industry and its institutional framework. There is discussion about “recent reforms” (many of which never eventuated, or were implemented only to be undone at a future date), National Forest Policy and the Regional Forest Agreements (RFA), the 2020 Plantation Vision, National Competition Policy, and Australian Accounting Standard for Self-Generating and Regenerating Assets (AAS 35). But within all this discussion there is little said about competitive neutrality. For example the discussion about the RFAs says nothing about if or how CN was dealt with within the RFAs.

As for the 1995 National Forest Policy it has never been implemented; and it contains no discussion at all about competitive neutrality.

In fact one of the key objectives of the RFA process should have been to set the State forest agencies on a level competitive playing field with each other AND private forest growers; with the objective to become profitable or cease to exist.

Unfortunately that did not happen; in my opinion a major failure of the RFA process.

There is considerable discussion in the report about Australian Accounting Standard AAS 35 ending with this classic quote:

AAS 35 provides a consistent framework for forest asset valuations across jurisdictions, but gives forest agencies considerable flexibility in implementing it. This has led to differences in asset valuations between agencies, and has particular implications for the implementation of CN by forest agencies.

In other words, never mind the level playing field!!

3 Application of CN to forestry

Chapter 3 talks about the implementation, monitoring and reporting of CN across Australian State forest agencies.

Progress in implementing CN is mixed. Jurisdictional differences in the application of CN to forestry agencies include the:

- institutional models within which CN compliance is being pursued;

- pricing and log allocation mechanisms;

- transparency of CSO funding;

- determination of target rates of return;

- allocation of overheads to commercial wood outputs (see box 3.1);

- approaches to achieving regulatory equivalence;

- monitoring arrangements; and

- asset valuation methodology used.

In other words the State forest agencies cannot even create a level playing field between themselves, let alone with private forest growers. So much for National Forest Policy!

[CN] Monitoring arrangements vary across jurisdictions [States].

In Tasmania, Forestry Tasmania is subject to monitoring by the State’s Prices Oversight Commission [now the Office of the Tasmanian Economic Regulator]. It also provides quarterly reports to Treasury on performance against agreed indicators.

Clearly no one is doing any monitoring or reporting in Tasmania. Go to the websites of either of these organisations (OTER or Treasury) and you will find NO information about CN monitoring or reporting by Forestry Tasmania. Forestry Tasmania’s own website contains NO mention of CN policy, objectives or performance.

http://www.economicregulator.tas.gov.au/

https://www.treasury.tas.gov.au/

All State government forest agencies should be required by law to have the exact same competitive neutrality policies, objectives, monitoring and reporting procedures. Otherwise the National Competition Policy is just wasted paper.

The report spends considerable time discussing whether logs are being sold at their ‘full’ market value, without the obvious answer that full contestable market value of public forest assets needs to be regularly and transparently determined “by the market”.

4 Log pricing issues

Over the last twenty years, there has been considerable evidence to suggest that forest agencies have frequently sold logs at less than their full market value. … evidence suggests that, in the past, royalties for sawlogs from State forests have often been some 20 to 70 per cent below their market value.

This doesn’t mean log underpricing began in the 1980s. It’s just that in the 1980s some people began to think this was a serious issue. Some people still think it is still a serious issue.

In 2016 the issue of log prices and marketing from State Government forest agencies remains unresolved. Deliberate underpricing continues unabated. Both Western Australia and Victoria started to go down the road towards market-based log sales and pricing, but changes in State governments saw those policies reversed.

In a fully competitive market environment, a sawmill [or other wood processor] will compete against other processors for log supplies from growers…. In practice, the market for logs sourced from State forests [or other growers] cannot always be regarded as fully competitive.

This market situation is no different to any other primary industry [cows, milk, apples, cabbages, etc.].

One of the issues around State forest agencies is that only wood processors are allowed to purchase public forest assets. Organisations that may wish to purchase public forest assets such as carbon sequestration or conservation are deliberately excluded from the market. This is not the case with privately owned forests in Australia. This is a deliberate breach of CN principles. Why can’t public forest assets be sold to the highest bidder (subject to certain management constraints)?

The Report talks about the various difficulties of determining real market prices for logs.

The Report fails to discuss issues around market and price transparency.

Section 4.3 (p. 36) discusses the impact of underpricing on private forest growers.

The major concern expressed about the price of logs sold by forestry agencies has related to underpricing. Whatever the underlying reason, allegations of underpricing [by State forest agencies] have frequently been cited as a factor impeding the development of private wood growing enterprises.

And

Recent reforms have created incentives for forest agencies to price logs on a more commercial basis. Consequently, it is possible that other factors may now have a greater impact on private growers than underpricing by forest agencies.

In 2001 that was wishful thinking. In 2016 it’s a bad joke!

The Report then discusses how underpricing of logs has left the Australian wood processing industry inefficient and uncompetitive, and therefore unable to pay full market prices for logs. It’s a debilitating spiral to bankruptcy.

A priori, the application of CN would be expected to reduce the incidence of log underpricing, because it requires forest agencies to act more commercially by charging prices that cover all the costs of growing and managing the forest, including a commercially acceptable return to the land and timber assets. This should help ensure that the full market value is realised for logs sold by State forestry agencies.

Lots of hope and optimism with little evidence in 2001 that CN reforms were really being implemented. In 2016 we know that hope was misplaced.

5 CN and the broader policy context

The implementation of CN in forestry will contribute to better cost recovery and pricing policies, and hence a more efficient and better managed public forest estate.

We haven’t seen any evidence of this in the last 15 years!!

It is often argued that the use of competitive tendering (or auctions) for the sale of logs would lead to higher prices because processors would be forced to pay the ‘true’ valuation of the logs.

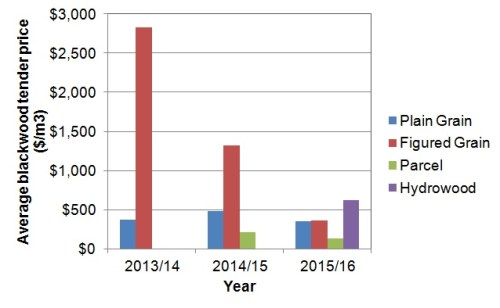

Outcomes from the relatively few auctions held to date suggest that a competitive market could also lead to greater differentials in log prices.

In other words premium timbers like blackwood would achieve much higher prices than they do under the current system of Government-set prices. Either that or hardwood sawlogs and pulpwood would be at give-away prices.

The role of secondary markets for harvesting rights may be of greater significance in achieving more competitive log pricing in such [one seller/grower, one buyer] markets. Competitive secondary markets for log entitlements would strengthen the processing sector’s incentive to operate efficiently.

Currently, harvesting rights [to public native forest] can only be held by wood processors. However, there would seem to be no reason why parties other than wood processors should not be able to bid for, and hold, such rights. If a timber right was modified to become a right to appropriate all the values of the forest, then holders may be better able to balance all possible uses — particularly in light of the potential development of some markets for environmental services.

Private forest growers are not subject to such market restrictions so why are State forest agencies?

There is very little published information on [log] prices realised by forest agencies. …[log] pricing policies and the terms on which harvesting licenses are allocated are generally confidential.

These are public assets being sold and the public has absolutely no right to understand the basis on which they are commercially managed!!

In the United States, the Department of Agriculture regularly publishes detailed information on stumpage prices (royalties), fob mill prices, harvest rates and sustainable harvest rates by species and region (Warren 2000). While the relatively small size of the Australian industry may prevent the publication of statistics in the same level of detail without breaching confidentiality, the limited information available in Australia denies the community information on a very significant natural asset and inhibits scrutiny of the pricing practices of State forest agencies. This increases the difficulties in assessing the performance of these agencies. At the same time, the absence of public information on market prices and conditions itself may constitute an impediment to private investment in forestry — information about farmgate or market prices is readily available to potential investors in most other natural resource and primary industries.

Overall it is not a great report. It could have been better.

Here’s my thoughts on a few other CN-related issues not discussed in the report:

Public benefit

The NCP allows State Governments to ignore CN principles if they claim public benefit overrides commercial interests. In 2001 when most wood grown and sold in Australia came from State forest agencies this was pretty easy. However in 2016 the reverse is now true, most wood now grown and sold in Australia comes from private forest growers. The public benefit from being a minor player in the forest industry is much more difficult to argue. Growing trees for wood production is now very definitely a commercial business not a community service.

Transparency

One of the fundamental issues around competitive neutrality is that it must be transparent. Private businesses that compete against Government businesses must be able to clearly and readily see that they are operating on a level playing field. The PC Report says:

The focus on cost recovery, and the trend toward greater transparency and accountability of public agencies in their management of public resources, has encouraged forest agencies to evaluate their forest management practices in terms of their impacts on efficiency and financial performance.

Otherwise the Report is generally critical of State governments and State forest agencies in their lack of CN transparency.

Log Export

There always seems to be strong community concern around the export of native forest logs. But the concept of competitive neutrality means that whatever markets are available to private tree growers must also be available to public forest managers. That is the level playing field. If private forest growers look to improve their profitability through log export markets, then the same must be available to the State forest agencies, including the export of sawlogs and specialty timbers. If high value log exports are banned then the viability of commercial native forest management may be compromised. Unfortunately the PC report does not discuss this issue.

Resource Security

Any legislation, regulation or policy that seeks to create a distinction between the public and private commercial forest is in breach of competitive neutrality principles. For example the concept of “resource security” is by definition a breach of competitive neutrality principles, because the concept is only applied to the public forest resource, never to the private resource. The Report even mentions resource security (p. 15) but fails to identify it as a breach of CN!

In New Zealand, where 100% of the forest industry is privately owned, they don’t talk about resource security. They do talk about the tensions between supply and demand, and how to manage fluctuations in supply and demand, but resource security is never mentioned.

State governments and State forest agencies continue to ignore their commitments and responsibilities under the National Competition Policy.

The so called level playing field has never been realised in the forest industry.

Vast sums of taxpayer’s money continue to be squandered on the industry. The most recent example is the Western Australian Government’s announcement of investing $21 million of taxpayers money in softwood plantation expansion without a business case. Presumably “public benefit” overrides the need for wise investment.

https://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/wa/a/32691021/wa-leads-nation-in-forestry/#page1

Blackwood

Of course with blackwood in Tasmania competitive neutrality has been thrown under a bus with the Government and Forestry Tasmania declaring “public benefit”; blackwood is officially a taxpayer-funded community service not a commercial activity.

It is time for the Productivity Commission to revisit and review the issue of competitive neutrality in the forest industry in Australia.

When will Tasmania get a fully commercial, profitable forest industry?

Competitive Neutrality in Forestry

In 2001 the Productivity Commission released a report into the competitive neutrality of the State government forest agencies in Australia.

http://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/forestry

The report makes for interesting reading 15 years after it was published.

So what is competitive neutrality?

Competitive neutrality (CN) means that state-owned and private businesses compete on a level playing field. This is essential to use resources effectively within the economy and thus achieve growth and development.

CN policy forms part of the 1995 Council of Australian Governments’ agreement on National Competition Policy (NCP).

CN policy aims to promote efficient competition between public and private businesses. Specifically, it seeks to ensure that government businesses do not enjoy competitive advantages (or suffer from a competitive disadvantage) over their private competitors simply by virtue of their public ownership.

The fact that the Productivity Commission felt the need to write such a report says a great deal about the forest industry in Australia. Remember this was in 2001 immediately after the Regional Forest Agreements (RFA) had been completed and signed.

Why weren’t competitive neutrality issues covered as part of the RFA reforms?

It is certainly my belief one of the major reasons we don’t have a thriving blackwood industry in Tasmania is the absence of competitive neutrality.

Here’s my precise of the report by chapter, and what I regard as some of the more salient points from a blackwood growers perspective.

1 Introduction

Forest products industries source wood from both public and privately managed forests, although public forests have traditionally accounted for the overwhelming bulk of wood supplies.

The situation has changed dramatically over the past 15 years with most wood grown and sold in Australia now coming from private forest growers. But State forest agencies continue to exert a significant influence on the industry especially around policy and politics.

Also the privatization of public plantation assets has introduced new distortions in the marketplace such as new owners being exempt from paying local Government rates and charges, competing against other private forest growers who do pay rates and charges. Local communities are now forced to subsidize the new private forest owners.

As forestry agencies are deemed to be significant government businesses, they are subject to CN. This requires them to:

To this list I would add:

There would certainly be other CN principles that could be added to this list.

2 Forestry background and institutional framework

Competitive neutrality is about a level playing field but the report provides little insight into the nature of the forest industry playing field and the numerous factors that impact the quality of the playing surface. For example there is a section in Chapter 2 discussing employment in the forestry sector, but no discussion on how sector employment impacts CN and the quality of the playing surface!

Chapter 2 provides a background summary of the industry and its institutional framework. There is discussion about “recent reforms” (many of which never eventuated, or were implemented only to be undone at a future date), National Forest Policy and the Regional Forest Agreements (RFA), the 2020 Plantation Vision, National Competition Policy, and Australian Accounting Standard for Self-Generating and Regenerating Assets (AAS 35). But within all this discussion there is little said about competitive neutrality. For example the discussion about the RFAs says nothing about if or how CN was dealt with within the RFAs.

As for the 1995 National Forest Policy it has never been implemented; and it contains no discussion at all about competitive neutrality.

In fact one of the key objectives of the RFA process should have been to set the State forest agencies on a level competitive playing field with each other AND private forest growers; with the objective to become profitable or cease to exist.

Unfortunately that did not happen; in my opinion a major failure of the RFA process.

There is considerable discussion in the report about Australian Accounting Standard AAS 35 ending with this classic quote:

AAS 35 provides a consistent framework for forest asset valuations across jurisdictions, but gives forest agencies considerable flexibility in implementing it. This has led to differences in asset valuations between agencies, and has particular implications for the implementation of CN by forest agencies.

In other words, never mind the level playing field!!

3 Application of CN to forestry

Chapter 3 talks about the implementation, monitoring and reporting of CN across Australian State forest agencies.

Progress in implementing CN is mixed. Jurisdictional differences in the application of CN to forestry agencies include the:

In other words the State forest agencies cannot even create a level playing field between themselves, let alone with private forest growers. So much for National Forest Policy!

[CN] Monitoring arrangements vary across jurisdictions [States].

In Tasmania, Forestry Tasmania is subject to monitoring by the State’s Prices Oversight Commission [now the Office of the Tasmanian Economic Regulator]. It also provides quarterly reports to Treasury on performance against agreed indicators.

Clearly no one is doing any monitoring or reporting in Tasmania. Go to the websites of either of these organisations (OTER or Treasury) and you will find NO information about CN monitoring or reporting by Forestry Tasmania. Forestry Tasmania’s own website contains NO mention of CN policy, objectives or performance.

http://www.economicregulator.tas.gov.au/

https://www.treasury.tas.gov.au/

All State government forest agencies should be required by law to have the exact same competitive neutrality policies, objectives, monitoring and reporting procedures. Otherwise the National Competition Policy is just wasted paper.

The report spends considerable time discussing whether logs are being sold at their ‘full’ market value, without the obvious answer that full contestable market value of public forest assets needs to be regularly and transparently determined “by the market”.

4 Log pricing issues

Over the last twenty years, there has been considerable evidence to suggest that forest agencies have frequently sold logs at less than their full market value. … evidence suggests that, in the past, royalties for sawlogs from State forests have often been some 20 to 70 per cent below their market value.

This doesn’t mean log underpricing began in the 1980s. It’s just that in the 1980s some people began to think this was a serious issue. Some people still think it is still a serious issue.

In 2016 the issue of log prices and marketing from State Government forest agencies remains unresolved. Deliberate underpricing continues unabated. Both Western Australia and Victoria started to go down the road towards market-based log sales and pricing, but changes in State governments saw those policies reversed.

In a fully competitive market environment, a sawmill [or other wood processor] will compete against other processors for log supplies from growers…. In practice, the market for logs sourced from State forests [or other growers] cannot always be regarded as fully competitive.

This market situation is no different to any other primary industry [cows, milk, apples, cabbages, etc.].

One of the issues around State forest agencies is that only wood processors are allowed to purchase public forest assets. Organisations that may wish to purchase public forest assets such as carbon sequestration or conservation are deliberately excluded from the market. This is not the case with privately owned forests in Australia. This is a deliberate breach of CN principles. Why can’t public forest assets be sold to the highest bidder (subject to certain management constraints)?

The Report talks about the various difficulties of determining real market prices for logs.

The Report fails to discuss issues around market and price transparency.

Section 4.3 (p. 36) discusses the impact of underpricing on private forest growers.

The major concern expressed about the price of logs sold by forestry agencies has related to underpricing. Whatever the underlying reason, allegations of underpricing [by State forest agencies] have frequently been cited as a factor impeding the development of private wood growing enterprises.

And

Recent reforms have created incentives for forest agencies to price logs on a more commercial basis. Consequently, it is possible that other factors may now have a greater impact on private growers than underpricing by forest agencies.

In 2001 that was wishful thinking. In 2016 it’s a bad joke!

The Report then discusses how underpricing of logs has left the Australian wood processing industry inefficient and uncompetitive, and therefore unable to pay full market prices for logs. It’s a debilitating spiral to bankruptcy.

A priori, the application of CN would be expected to reduce the incidence of log underpricing, because it requires forest agencies to act more commercially by charging prices that cover all the costs of growing and managing the forest, including a commercially acceptable return to the land and timber assets. This should help ensure that the full market value is realised for logs sold by State forestry agencies.

Lots of hope and optimism with little evidence in 2001 that CN reforms were really being implemented. In 2016 we know that hope was misplaced.

5 CN and the broader policy context

The implementation of CN in forestry will contribute to better cost recovery and pricing policies, and hence a more efficient and better managed public forest estate.

We haven’t seen any evidence of this in the last 15 years!!

It is often argued that the use of competitive tendering (or auctions) for the sale of logs would lead to higher prices because processors would be forced to pay the ‘true’ valuation of the logs.

Outcomes from the relatively few auctions held to date suggest that a competitive market could also lead to greater differentials in log prices.

In other words premium timbers like blackwood would achieve much higher prices than they do under the current system of Government-set prices. Either that or hardwood sawlogs and pulpwood would be at give-away prices.

The role of secondary markets for harvesting rights may be of greater significance in achieving more competitive log pricing in such [one seller/grower, one buyer] markets. Competitive secondary markets for log entitlements would strengthen the processing sector’s incentive to operate efficiently.

Currently, harvesting rights [to public native forest] can only be held by wood processors. However, there would seem to be no reason why parties other than wood processors should not be able to bid for, and hold, such rights. If a timber right was modified to become a right to appropriate all the values of the forest, then holders may be better able to balance all possible uses — particularly in light of the potential development of some markets for environmental services.

Private forest growers are not subject to such market restrictions so why are State forest agencies?

There is very little published information on [log] prices realised by forest agencies. …[log] pricing policies and the terms on which harvesting licenses are allocated are generally confidential.

These are public assets being sold and the public has absolutely no right to understand the basis on which they are commercially managed!!

In the United States, the Department of Agriculture regularly publishes detailed information on stumpage prices (royalties), fob mill prices, harvest rates and sustainable harvest rates by species and region (Warren 2000). While the relatively small size of the Australian industry may prevent the publication of statistics in the same level of detail without breaching confidentiality, the limited information available in Australia denies the community information on a very significant natural asset and inhibits scrutiny of the pricing practices of State forest agencies. This increases the difficulties in assessing the performance of these agencies. At the same time, the absence of public information on market prices and conditions itself may constitute an impediment to private investment in forestry — information about farmgate or market prices is readily available to potential investors in most other natural resource and primary industries.

Overall it is not a great report. It could have been better.

Here’s my thoughts on a few other CN-related issues not discussed in the report:

Public benefit

The NCP allows State Governments to ignore CN principles if they claim public benefit overrides commercial interests. In 2001 when most wood grown and sold in Australia came from State forest agencies this was pretty easy. However in 2016 the reverse is now true, most wood now grown and sold in Australia comes from private forest growers. The public benefit from being a minor player in the forest industry is much more difficult to argue. Growing trees for wood production is now very definitely a commercial business not a community service.

Transparency

One of the fundamental issues around competitive neutrality is that it must be transparent. Private businesses that compete against Government businesses must be able to clearly and readily see that they are operating on a level playing field. The PC Report says:

The focus on cost recovery, and the trend toward greater transparency and accountability of public agencies in their management of public resources, has encouraged forest agencies to evaluate their forest management practices in terms of their impacts on efficiency and financial performance.

Otherwise the Report is generally critical of State governments and State forest agencies in their lack of CN transparency.

Log Export

There always seems to be strong community concern around the export of native forest logs. But the concept of competitive neutrality means that whatever markets are available to private tree growers must also be available to public forest managers. That is the level playing field. If private forest growers look to improve their profitability through log export markets, then the same must be available to the State forest agencies, including the export of sawlogs and specialty timbers. If high value log exports are banned then the viability of commercial native forest management may be compromised. Unfortunately the PC report does not discuss this issue.

Resource Security

Any legislation, regulation or policy that seeks to create a distinction between the public and private commercial forest is in breach of competitive neutrality principles. For example the concept of “resource security” is by definition a breach of competitive neutrality principles, because the concept is only applied to the public forest resource, never to the private resource. The Report even mentions resource security (p. 15) but fails to identify it as a breach of CN!

In New Zealand, where 100% of the forest industry is privately owned, they don’t talk about resource security. They do talk about the tensions between supply and demand, and how to manage fluctuations in supply and demand, but resource security is never mentioned.

State governments and State forest agencies continue to ignore their commitments and responsibilities under the National Competition Policy.

The so called level playing field has never been realised in the forest industry.

Vast sums of taxpayer’s money continue to be squandered on the industry. The most recent example is the Western Australian Government’s announcement of investing $21 million of taxpayers money in softwood plantation expansion without a business case. Presumably “public benefit” overrides the need for wise investment.

https://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/wa/a/32691021/wa-leads-nation-in-forestry/#page1

Blackwood

Of course with blackwood in Tasmania competitive neutrality has been thrown under a bus with the Government and Forestry Tasmania declaring “public benefit”; blackwood is officially a taxpayer-funded community service not a commercial activity.

It is time for the Productivity Commission to revisit and review the issue of competitive neutrality in the forest industry in Australia.

When will Tasmania get a fully commercial, profitable forest industry?

Leave a comment

Posted in Commentary, Forestry Tasmania, Markets, Politics, Prices

Tagged competitive neutrality, Forest Products Commision, Forestry QLD, Forestry Tasmania, NSW Forestry Corporation, Productivity Commission, Vicforests